The Berlin Wall: A Day that Changed the World

Back when Quercus books was starting out (even before they were called Quercus) I wrote a piece for them as proof of concept for a planned volume called Days that changed the World (to follow on from the successful Speeches that changed the World). In the end it became a book by Hywel Williams. I really liked my sample piece, mocked up for the Frankfurt bookfair, and now, on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, I’d like other people to be able to read it.

“Every wall will fall some day”

It was 6.57 pm on Thursday 9 November 1989. In a press conference Günter Schabowski, head of the Berlin section of East Germany’s ruling party the SED (Socialist Unity Party of Germany), was trying to answer a question put by an Italian journalist.

Earlier that day at the Politburo (Cabinet) meeting, the continued hemorrhaging of East German citizens to the West, through the increasingly open borders of its communist allies, had been discussed. It was decided that a system of permits would be introduced to allow travel into West Berlin. It was Günter Schabowski’s role to answer questions at the subsequent press conference, but he had only returned from holiday towards the end of the meeting and so missed much of the discussion. The question the journalist had asked was about this very issue of travel into West Berlin, so Schabowski was handed a piece of paper to help him give an answer. It was a press release intended for publication the following day. No one meant for him to read it out loud but that’s what he did. He was then asked when this would actually happen. Unaware of the proposed timetable he mistakenly announced to the surprised group of journalists before him that ‘this is immediate, without delay’.

‘As far as I know, this is immediate, without delay’ Günther Schabowski, Head of Berlin SED, 6:57pm

Within minutes the news wire services AP (Associated Press) and DPA (the German Press Agency) were reporting that East Germany had opened its borders to the West. The citizens of East Berlin flocked to the crossing points in the Wall hoping to gain access. Outnumbered and unprepared the border guards didn’t know what action to take. Telephone calls to their superiors apparently said ‘we’re flooding’ as they held back the ever-increasing crowds. Finally, around 10.30 pm at Bornholmer Strasse they bowed to the inevitable and opened the crossing. After 10,315 days stretching across 28 years the antifaschistischer Schutzwall (Anti-Fascist Protection Wall), the physical symbol of the Iron Curtain across Europe, had finally fallen.

‘I won’t believe it until I’m on the other side’ unknown East Berlin woman

‘We’re flooding’ East German border police

The 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall was the pivotal moment in a dramatic year across Europe. This followed in the wake of the new philosophies of Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring) coming from Mikhail Gorbachev in The Kremlin. The Poles with their powerful Solidarity trades union were impatient for reform and on 5 April the communist government there agreed to hold free elections. In May, Gorbachev came to West Germany to meet with Chancellor Kohl. He informed Kohl that the Brezhnev doctrine was over – that Russia was no longer prepared to use force to control the satellite states that comprised the Soviet Union. At once the government in Hungary announced its intention to begin the dismantling of the Iron Curtain along the border with Austria. The floodgates were open.

East Germans began pouring into Hungary en route to what they hoped was a new life in the West. The scale of the exodus was unprecedented. Some were allowed through into Austria while others who were turned back ended up camping in the grounds of the West German Embassy in Prague in Czechoslovakia.

A weekly peace vigil had begun on Mondays in the East German city of Leipzig. At first the numbers were small, but despite sometimes violent police action they grew. On 4 September there were a thousand demonstrators – by 16 October there were 120,000. Loudspeakers proclaimed their words of opposition throughout the city:

We, the people, demand:

- the right to free access of information

- the right to open political discussions

- the freedom of thought and creativity

- the right to maintain a plural ideology

- the right to dissent

- the right to travel freely

- the right to exert influence over government authority

- the right to re-examine our beliefs

- the right to voice an opinion in the affairs of state

The Leipzig protests

Gorbachev had returned to Berlin as guest of honour for the 40th anniversary of the East German state on 7 October. In front of the Palace of the Republic the celebrations turned to protest as the crown cried out for Gorbachev to help them. The demonstration was broken up by the police with a thousand arrests. In a warning to the SED Gorbachev announced ‘Wer zu spät kommt, den bestraft das Leben’ (whoever comes too late is punished by life). In East Germany this was seen as a tacit acknowledgement that the old order was over. Following Gorbachev’s comments and the ever-increasing demonstrations against him, East German President Eric Honecker, who as late as June had claimed the Wall would last for another ‘50 or 100 years’, resigned on 18 October.

Honecker was the original builder of the Wall. More than two and a half million East Germans had escaped to West Germany between 1949 and 1961, an unsustainable drain on the communist state’s resources. Because of this the first East German President, Walter Ulbricht, had secretly decided a wall must be built. He sought the then Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s permission to make his plan a reality. At midnight on the morning of Sunday 13 August 1961, Honecker, responsible for security on the SED Central Committee and so the overseer of the construction of the Wall, sealed the border with West Berlin while the citizens in the east slept. In preparation for the day he had stored 25 miles (40 km) of barbed wire and thousands of fence posts in barracks around the city. This was brought out and the Wall was erected behind a line of 25,000 armed police, posted every six feet along the border.

The resignation of Honecker saw him replaced by another hardliner, Egon Krenz, but the exodus from East Germany continued apace. On Tuesday 7 November the government of East Germany resigned en masse appealing to the public that ‘in this serious situation, all energies be concentrated on keeping up all functions indispensable to the people, society and the economy.’ The plan was that the ministers would remain in office until a new government could be formed. The next day the entire Politburo also resigned. However, the Central Committee of the SED unanimously re-elected Egon Krenz as leader. That afternoon party members elected a new Politburo who would meet for the first time the following day under Krenz’s leadership. The rapid changes in the administration and personnel were perhaps the reason for Günter Schabowski’s confused announcement on the fateful evening.

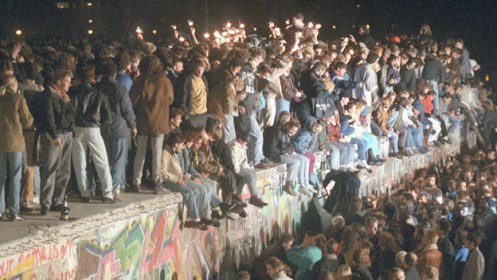

As night fell on 9 November a street party spread all across West Berlin that lasted several days. As each East German Trabi drove across Checkpoint Charlie its driver honked its horn and was cheered by the masses. East German border guards joined the celebrations and were presented with flowers by delighted West Berliners. East Germans were pouring into West Berlin with no money, so it was quickly announced that possession of an East German passport would entitle the bearer to free public transport and museum admission across the city.

‘Berlin was out of control. There was no more government, neither in East nor in West. The police and the army were helpless. The soldiers themselves were overwhelmed by the event. They were part of the crowd. Their uniforms meant nothing. The Wall was down.’ From a personal account by Andreas Ramos, a Dane in Berlin

‘Soon after the announcement was made, my family and I went to the wall with hammers and chisels in order to help knock it down. There were hundreds of people there already. I was surprised at just how difficult it was to break a piece of wall off: it was made of such hard material. Looking at gaps which others before me had managed to create, I could see the thick iron wires which were between the concrete layers making up the wall. One thing I did notice about the wall was that the West side was covered in graffiti and the East was perfectly clean: the East Berliners were not allowed near the wall. I had fun knocking away at the wall, and did manage to break of small chunks, which I still have today.’ From a personal account by Louise Hopper, then a 14 year old English girl living in West Berlin

Tear down the wall

The next day, Friday, saw the announcement of free elections in East Germany to take place the following year. Then, on Sunday 12 November, the Wall was opened at the historic Potsdamer Platz (Potsdam Square) by the mayors from each half of the previously divided city. Walter Momper, Mayor of West Berlin proclaimed ‘Potsdam Square is the old heart of Berlin and it will beat again as it used to.’ Six weeks later the historic Brandenburg Gate, was also reopened in front of enormous crowds.

Systematic demolition of the Wall began on 13 June the following year and Germany was finally reunited on 3 October 1990. However, a watching world that had been caught in the grip of the Cold War for so long remembers 9 November 1989 as the day it ended – the day the Berlin Wall fell.

Factfile

Erected: 13 August 1961

Total Length: 96 miles (155 km)

inside Berlin: 26.8 miles (43.1 km)

between Berlin and East Germany: 70 miles (112 km)

Watch Towers: 302

Concrete Shelters: 22

Border Guards: 14,000

Successful escapees: 5,043 (incl. 574 members of armed forces)

Escapees killed: 239

Soldiers and policemen killed: 27

Subscribe to Keith Mansfield's RSS feed

Subscribe to Keith Mansfield's RSS feed